And our neighbor got a picture.

And our neighbor got a picture.

Which he got right from Paul-

The natural person has no room for the gifts of God’s Spirit; to him they are folly; he cannot recognise them, because their value can be assessed only in the Spirit. The spiritual person, on the other hand, can assess the value of everything, and that person’s value cannot be assessed by anybody else. For: who has ever known the mind of the Lord? Who has ever been his adviser? But we are those who have the mind of Christ. (1 Cor. 2:14-16)

Like it or not, Paul’s assertion that only those gifted with the Spirit understand the gifts of the Spirit is true. Dwelling outside the hermeneutical circle doesn’t mean one is a bad historian. But it does mean one is a terrible theologian and a worse exegete. All protestations to the contrary notwithstanding.

Karl Barth had a very lively sense of humour. And at times his humour was decidedly wicked (in the best sense of the word), not least of all when he made fun of other theologians with whom he disagreed. He was, for instance, always making fun of his old friend Rudolf Bultmann. One of the most entertaining features of CD volume IV is Barth’s constant lampooning of Bultmann—while Bultmann himself is almost never named, he is the object of numerous wicked jokes about mythology, hermeneutics, self-understanding, demythologising, and so on.

Barth’s published letters also contain many funny characterisations of other theologians. For instance, after reading Pannenberg’s new book Jesus—God and Man, Barth wrote to Helmut Gollwitzer that “even the ravens I see on the top of a high tree from my seat here, though they do not do ‘biblical work,’ … do not regard this work on christology as a good book.”

But funnier (and more wicked) still is his characterisation of Dorothee Soelle. In another letter to Gollwitzer, Barth describes Dorothee Soelle as a woman “of great brilliance and even greater lack of understanding!” And in a letter to Karl Rahner, Barth says that Soelle is “a lady of whom the only thing one can really say is that that woman should keep silence in the church.” Ouch!

Posted originally by Ben Myers back in 2006. That’s before most of the people in America who talk about Barth these days were out of High School.

🙂

If ever there were proof of the validity of the Roman Catholic concept of Ex opere operato, Karl Barth is it.

If ever there were proof of the validity of the Roman Catholic concept of Ex opere operato, Karl Barth is it.

Mutatis mutandis of course.

Ex opere operato refers, in Catholic theology, to the fact that the sacraments are efficacious in and of themselves and do not depend on the efficacy of the Priest administering them. The Priest might be a womanizing swine, but the Sacraments remain sacramental.

Mutatis mutandis, Barth’s theology is and remains brilliant in spite of the fact that he was a womanizing swine.

If God were waiting for the perfect vessel through which to speak and act he would have needed to wait till August 29, 1960. Let the reader understand.

Anyway, Barth was a pig. But his theology is divinely inspired.

It may be important- nay- it is important to learn that

Doch anders als viele Menschen denken, wurden sie nicht von der NSDAP oder einem Ministerium organisiert, sondern von der Deutschen Studentenschaft, die sich, so vermuten Wissenschaftler, damit den Nationalsozialisten andienen wollten.

German students came up with the bright idea to burn all those books. Remarkable. One of the most senseless acts of Nazi history wasn’t thought up by the leadership- it was an act of University students… the very people who ought to know better.

The essay from which that snippet is drawn is very much worth reading it its entirety.

After Charlotte von Kirschbaum moved into Barth’s house, Barth signed his notes to her in the following ways1:

or, later, simply

from 1931 occasionally:

for example, on 1 August.

In 1934, he writes from Rome:

and finally, in a language style of a modern text message, apart from ‘I l. y. s. m.’ once also

______________

1Biography and theology. On the connectedness of theological statements with life on the basis of the correspondence between Karl Barth and Charlotte von Kirschbaum (1925–1935), by Susanne Hennecke

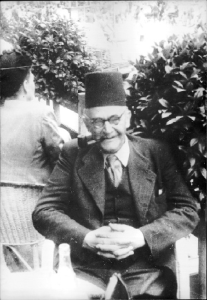

Der Schweizer Karl Barth gilt als das theologische Genie des 20. Jahrhunderts. Er hat die Bekennende Kirche mit am stärksten beeinflusst – auch dort, wo man sich seiner Radikalität nicht anschloss. Obgleich konsequent reformierter Theologe hat er doch über die Konfessionsgrenzen hinweg den evangelischen „Kirchenkampf“ maßgeblich bestimmt, zunächst als Theologieprofessor in Bonn, später von Basel aus, wo er für viele Angehörige der Bekennenden Kirche die prominenteste Bezugsperson blieb.

Der Schweizer Karl Barth gilt als das theologische Genie des 20. Jahrhunderts. Er hat die Bekennende Kirche mit am stärksten beeinflusst – auch dort, wo man sich seiner Radikalität nicht anschloss. Obgleich konsequent reformierter Theologe hat er doch über die Konfessionsgrenzen hinweg den evangelischen „Kirchenkampf“ maßgeblich bestimmt, zunächst als Theologieprofessor in Bonn, später von Basel aus, wo er für viele Angehörige der Bekennenden Kirche die prominenteste Bezugsperson blieb.

Geboren am 10. Mai 1886, war Barth fest im religiösen Milieu seiner Heimatstadt Basel verwurzelt. Schulzeit und Anfänge des Theologiestudiums verbrachte er in Bern, wechselte später nach Berlin, Tübingen und Marburg. Nach Vikariat und Examen 1908 kam er als Redaktionsgehilfe zur Marburger Zeitschrift „Die Christliche Welt“. Von nachhaltiger Bedeutung wurde ab 1911 seine erste Pfarrstelle in Safenwil im Schweizer Kanton Aargau, wo er mit den sozialen Problemen des Arbeiteralltags konfrontiert wurde. In dieser Zeit intensiver Unterrichts- und Predigtarbeit erfolgte der endgültige Bruch mit der Liberalen Theologie und die Initiative zu einem neuen theologischen Modell – in Gestalt von Barths dort niedergeschriebenem „Römerbrief“ (1918/19). Dieses Buch gilt als Gründungsdokument der Dialektischen Theologie, die den unendlich großen Abstand zwischen Gott und Mensch betont. Noch einflussreicher wurde die zweite Fassung, die Barth 1922 als Honorarprofessor in Göttingen schrieb. Dort gründete er mit Freunden die Zeitschrift „Zwischen den Zeiten“ als Organ der neuen Richtung. Von 1925 bis 1930 folgte eine Professur in Münster, ab 1930 in Bonn, wo die jahrzehntelange Arbeit an der „Kirchlichen Dogmatik“ begann.

Nach der nationalsozialistischen Machtübernahme wurde Barth rasch eine führende Autorität des Kirchenkampfes. Seine Schrift „Theologische Existenz heute!“ (1933) trug maßgeblich zu einem Rückgang der nationalen Begeisterung unter protestantischen Pfarrern und zu einer Rückbesinnung auf Bibel und Bekenntnis bei. Die „Barmer Theologische Erklärung“ (1934) ist wesentlich von ihm bestimmt. Doch bald mochten große Teile der Bekennenden Kirche Barths radikale Absage an die nationalsozialistische Kirchenpolitik und generell an Hitlers Staat in der von ihm eingeforderten Konsequenz nicht mehr mitvollziehen. Als ihm wegen Eidesverweigerung ein Dienststrafverfahren angehängt wurde, blieb öffentlicher Protest der Bekennenden Kirche aus. Barth zog sich, nachdem er 1935 vorzeitig in den Ruhestand versetzt wurde, auf eine Professur nach Basel zurück. Als „Schweizer Stimme“ ermunterte er die Deutschen fortan nachdrücklich zum aktiven Widerstand.

Nach dem Krieg führte Barth die theologische Arbeit fort, vor allem in Gestalt seiner „Kirchlichen Dogmatik“, die er allerdings nicht mehr abschließen konnte. Bis zu seinem Tod am 10. Dezember 1968 blieb er eine der gefragtesten Autoritäten des Protestantismus.

Or, more thoroughly,

Unterdessen hat gerade die überhandnehmende kalte Sachlichkeit des militärischen Tötens, das Raffinement und die massenhafte Wirkung, zum Teil auch die Abscheulichkeit seiner Methoden, Instrumente und Maschinen und seine Ausdehnung auf die feindliche Zivilbevölkerung dafür gesorgt, daß, wer Krieg sagt, wissen müßte, daß er damit schlicht und eindeutig töten sagt: töten ohne Glanz, ohne Würde, ohne Ritterlichkeit, ohne Schranke und Rücksicht nach irgendeiner Seite. Der Ruhm des sogenannten «Soldatenhandwerkes», das eben heute beiläufig zum direkt oder indirekt ausgeübten «Handwerk» eines Jeden geworden ist, kann in unseren Tagen nur noch von den Resten jener alten, schon damals fadenscheinigen Illusionen leben. Es wäre schon viel gewonnen, wenn man sich angesichts der Tatsachen endlich ganz nüchtern dazu bekennen würde, daß, was auch der Zweck und allenfalls das Recht des Krieges sein mag, sein Mittel heute jedenfalls ohne Hülle und Scham dies ist, daß nicht nur Einzelne, nicht nur irgendwelche «Heere», sondern die ganzen Völker als solche sich gegenseitig mit allen Mitteln ans Leben wollen. Die Möglichkeit der Atom- oder Wasserstoffbombe hat eigentlich nur noch gefehlt, um die Selbstenthüllung des Krieges in dieser Hinsicht vollständig zu machen. — Karl Barth, KD III/4, 518f

After Zwingli, Brunner, and Luther he is my favorite theologian of all time. 4th place is pretty good.

So, then, why do I harass his followers and sycophants? Because admiring and loving Barth too often become slathering over and idolizing Barth. Barth would hate that. Any theologian should hate that.

Any theologian worth their salt says with the Angel of Revelation- ‘don’t worship me, worship God’. Barth’s followers seem exceedingly likely to forget that little truth.

Icons are made to be destroyed. Iconoclasts do that. And I can’t help it. I was born this way.

I really do love Barth. I just don’t love his worshipers.

Since it’s Barth’s birthiversary allow me to recommend the best bio of Barth yet written:

From the beginning of his career, Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886-1968) was often in conflict with the spirit of his times. While during the First World War German poets and philosophers became intoxicated by the experience of community and transcendence, Barth fought against all attempts to locate the divine in culture or individual sentiment. This freed him for a deep worldly engagement: he was known as “the red pastor,” was the primary author of the founding document of the Confessing Church, the Barmen Theological Declaration, and after 1945 protested the rearmament of the Federal Republic of Germany.

From the beginning of his career, Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886-1968) was often in conflict with the spirit of his times. While during the First World War German poets and philosophers became intoxicated by the experience of community and transcendence, Barth fought against all attempts to locate the divine in culture or individual sentiment. This freed him for a deep worldly engagement: he was known as “the red pastor,” was the primary author of the founding document of the Confessing Church, the Barmen Theological Declaration, and after 1945 protested the rearmament of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Christiane Tietz compellingly explores the interactions between Barth’s personal and political biography and his theology. Numerous newly-available documents offer insight into the lesser-known sides of Barth such as his long-term three-way relationship with his wife Nelly and his colleague Charlotte von Kirschbaum. This is an evocative portrait of a theologian who described himself as “God’s cheerful partisan,” who was honored as a prophet and a genial spirit, was feared as a critic, and shaped the theology of an entire century as no other thinker.

You must be logged in to post a comment.