While some Christians have embraced the relationship between faith and the arts, the Reformed tradition tends to harbor reservations about the arts.

While some Christians have embraced the relationship between faith and the arts, the Reformed tradition tends to harbor reservations about the arts.

However, among Reformed churches, the Neo-Calvinist tradition—as represented in the work of Abraham Kuyper, Herman Dooyeweerd, Hans Rookmaaker, and others—has consistently demonstrated not just a willingness but a desire to engage with all manner of cultural and artistic expressions.

This volume, edited by art scholar Roger Henderson and Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker, the daughter of art historian and cultural critic Hans Rookmaaker, brings together history, philosophy, and theology to consider the relationship between the arts and the Neo-Calvinist tradition. With affirmations including the Lordship of Christ, the cultural mandate, sphere sovereignty, and common grace, the Neo-Calvinist tradition is well-equipped to offer wisdom on the arts to the whole body of Christ.

Art is well outside my wheelhouse. While I am happy to say that I took an ‘art appreciation’ class in College, I don’t remember a thing about it other than the fact that the Professor showed us slides of important artwork and talked about what they meant and why they were made. Paintings, sculptures, music, books, all aspects of art were covered.

It was a good course. But that was the last time I took any time to think seriously about art and artistry.

So I was glad to look in that direction again. After… too many decades to count really. And I’m glad that this book was the place I looked.

The book doesn’t discuss art history though. It instead focuses on art as it was and has been viewed and utilized in Calvinist circles. The book’s contents serve as a roadmap to where the volume wishes to take readers:

Part One: Roots

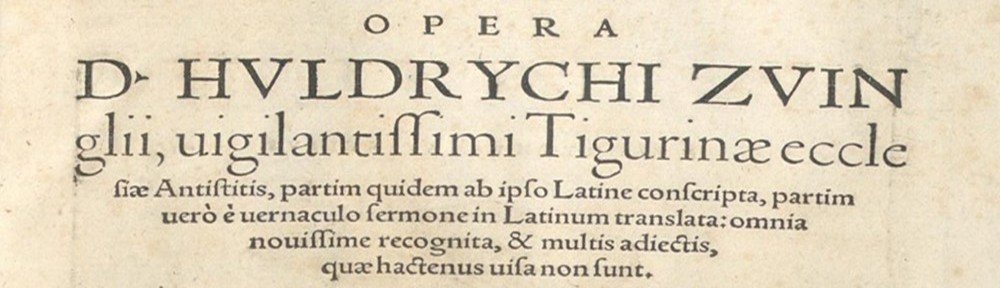

- Geneva’s Artistic Legacy: From Calvin to Today, Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker

- Calvin and the Arts: Pure Vision or Blind Spot?, Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin

- Rumors of Glory: Abraham Kuyper’s Neo-Calvinist Theory of Art, Roger D. Henderson

- Dooyeweerd’s Aesthetics, Roger D. Henderson

Part Two: Art History

- Art, Meaning, and Truth, Hans R. Rookmaaker

- The Vocation of a Christian Art Historian: Strategic Choices in a Multicultural Context, E. John Walford

- More than Can Be Seen: Tim Rollins and K.O.S.’s I See the Promised Land, James Romaine

Part Three: Aesthetics

- The Halo of Human Imaginativity, Calvin Seerveld

- Rethinking Art, Nicholas Wolterstorff

- Imagination, Art, and Civil Society: Re-envisioning Reformational Aesthetics, Lambert Zuidervaart

- Art, Body, and Feeling: New Roads for Neo-Calvinist Aesthetics, Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin

Part Four: Theology and Art

- The Theology of Art of Gerardus van der Leeuw and Paul Tillich, Wessel Stoker

- The Elusive Quest for Beauty, William Edgar

- Fifty-Plus Years of Art and Theology: 1970 to Today, Victoria Emily Jones

There are also various excurses along the way. The whole is a helpful guide to the importance of art for Christian theological expression. Art, after all, is a good gift of God too, like medicine, and science, and all of the things that help make life better and more enjoyable. Art can even be the means by which God speaks to us.

This book serves, for me, as a healthy denunciation of the idea that Calvinism is dry and boring and uninterested in the things of this world and only focuses on the hereafter. That, of course, has always been a lie but it’s still a fairly wide held misconception.

There’s a bibliography of important further reading at the end of each chapter. There are illustrations. And, again, there are fascinating excurses. The two most incredible, to me, because of my love of their work, is that concerning Albrecht Durer and Matthias Grunewald.

Some of the material has appeared previously in English and in Dutch. Those familiar with it will not mind, as it is material worth repeating for them and worth seeing for the rest of us.

This is not only a commendable volume for the information it provides, but for the way in which it helps us all towards a fuller understanding of the intersection of art and theology. These two spheres of human endeavor have much to teach one another, and the rest of us.

You must be logged in to post a comment.