Category Archives: Zwingli

Zwingli For Today

Fun Facts From Church History: Zwingli’s ‘Zurich German’ Wasn’t Widely Understood

The dialect the good people of Zurich spoke was, and is, in many respects, quite unique (even now). Luther had problems with it and so did The Landgrave of Marburg.

The dialect the good people of Zurich spoke was, and is, in many respects, quite unique (even now). Luther had problems with it and so did The Landgrave of Marburg.

Consequently, on

May 7, 1529, [Zwingli wrote the Landgrave in the lead-up to the Marburg Colloquium] – “… that I address you in Latin I do it for this reason only because I fear that our Swiss tongue is strange to you” (viii., 663). So, also, to the same on July 14th he wrote: “I fear that if we meet I shall not be understood in my tongue. So I do not know whether it would not be better if we used Latin” (viii., 324).

At Marburg Luther constantly whined about Zwingli using Greek. He did so not to be a show-off (even though he could have done, being at that stage far better than Luther (though not than Melanchthon) at Greek and the best of the lot in Hebrew) but because the folk there assembled would have been lost had he spoken the language of his home.

Today With Zwingli: Redemption Means Change or it Means Nothing

When … Divine Majesty formed the plan of redeeming man, it did not intend that the world should persist and become inveterate in its wickedness. For if this had been the plan, it would have been better never to have sent a redeemer than to have sent one under such conditions that after redemption there should be no change from our former diseased state.

It would have been laughable if He to whom everything that is ever to be is seen as present had determined to deliver man at so great a cost, and yet had intended to allow him immediately after his deliverance to wallow in his old sins. He proclaims, therefore, at the start, that our lives and characters must be changed. For to be a Christian is nothing less than to be a new man and a new creature [2 Cor. 5:17]. — Huldrych Zwingli

Today With Zwingli: Über den ungesandten Sendbrief Fabers Zwinglis Antwort

On the 30th of April, 1526, Huldrych Zwingli published his Über den ungesandten Sendbrief Fabers Zwinglis Antwort. Zwingli had been forbidden by the Zurich Magistrates to attend the Baden Disputation (because they knew he would be killed) and when his friend Oecolampadius sent him a copy of Fabers ‘Answer’ to Zwingli’s reformatory efforts, Zwingli was forced to reply.

The title of the book itself is a swipe at Faber’s rather uncharitable behavior, for rather than sending Zwingli a copy of his own work, Faber failed to do so. It was simply customary, in the 16th century, to send your theological adversaries any work you produced which addressed theirs. Faber didn’t. So Zwingli swings away- ‘Concerning the Letter Faber Didn’t Send (To Me Directly!), Zwingli’s Answer!’

The book is itself made up of 65 short paragraphs (and some not so short) responding point by point to Faber’s critique. It is brutally direct and just the sort of thing that makes the 16th Century theologians so fun to read.

More Fun From Melanchthon

Zum Dritten, so ist Schweisz ein wild ungehalten Volk, und so es gewaltig wird, wird es mehr Kunheit und Frevel erzeigen, wie warlich Zwingli von vielen Sachen frevelich und heidnisch geredt. Derhalben wir uns billig vor der Schweiszer Gemeinschaft besorgen. – P.M.

Because the more you know…

Today With Zwingli

Three works were published by Zwingli on April 27-

Eine Antwort, Valentin Compar gegeben, 27. April 1525

Auszug aus des H. von H. Brief, 27. April 1531

Auszug aus dem Brief von dem S. v. H., 27. April 1531

The first addresses four pressing issues (of the day)- the Gospel, faith, images, and purgatory. The second and third are simple excerpts or brief citations of the works of others. The first is a theological declaration and the other two are little windows on Zwingli’s interests at the end of April, 1531. All three tell us a great deal about Zwingli.

In the first one, Zwingli addresses, point by point, the concerns of his interlocutor. Thusly:

In der vorred Valentin Compar.

“In massen sich ze verwundren, daß durch din wirde und ander die glertsten zuo diser zyt sölcher irtum sol erwachsen, billicher ze verhoffen wär, ob etwas irtumb vorhanden xin wäre, das dann der durch sölich gelerte lüth gantz hynweg thon sölte werden”.

Zuingly.

Diß ist die schwärest schmachred, die du uff mich thuost durch das gantz buoch hyn, aber verzych mir got all min sünd, als ich dir diß bresthafft wort verzigen hab; denn durch mich ghein irrtumb nie erwachsen ist noch gepflantzt, wiewol ich deß von minen mißgünneren seer gescholten wird. Mag aber by denselben min unschuld nit harfürkummen, wirt sy doch am letsten urteyl vor der gantzen welt ersehen werden in dem handel; sust bin ich ein armer sünder gnuog; gott kömm mir al weg ze hilff!

Go, read all three. Good times.

That Papal Pension of Zwingli’s

Ok, here are the facts- which cannot be seriously disputed:

Zwingli’s Papal Pension

Bullinger says (i., 8) that the Pope (Julius II.) gave Zwingli a pension, “for the purchase of books.” But this was a sort of euphemism, and was understood on both sides as binding him to some extent to the papal chair, for the Pope was not in the habit of giving pensions to men like Zwingli out of charity or admiration. Yet since Zwingli was then a loyal papalist he could with perfect propriety and in all good conscience accept it. The year of its first bestowal was probably 1512–13.

But when he came out as a severe critic of the papacy, as he did in 1517, then his acceptance was not proper, as he himself allows in the passages to be quoted. But he continued to take the papal pension till 1520, when it had become a public scandal and source of trouble, as his enemies were constantly throwing it in his teeth.

Like mean spirited people do today, I’ll interject… But back to our story-

Like mean spirited people do today, I’ll interject… But back to our story-

Why he took it was his poverty, which has been often pleaded in excuse for similar action. Chronologically, the first bit of writing which can be quoted in which he alludes to his fault in continuing to receive the pension is the dedication to the sermon on the Virgin Mary, which he published in 1522.

He says: “My connection with the Pope of Rome is now a thing of several years back. At the time it began it seemed to me a proper thing to take his money and to defend his opinions, but when I realised my sin I parted company with him entirely” (i., 86).

Next and more explicit was his confession in the “Exposition of the Articles” of the Zurich Disputation of January, 1523:

“I had for three years previous [to 1520] been preaching the Gospel with earnestness; on which account I received from the papal cardinals, bishops, and legates, with whom the city has abounded, many friendly and earnest counsels, with threats, or with promises of greater gifts and of benefices. These, however, have had no effect upon me. On the other hand, in 1517 I declined to receive the pension of fifty gulden, which they gave me yearly (yes, they wanted to make it one hundred gulden, but I would not hear to it), but they would not stop it until in 1520 I renounced it in writing. (I confess here my sin before God and all the world, that before 1516 I hung mightily upon the Pope and considered it becoming in me to receive money from the papal treasury. But when the Roman representatives warned me not to preach anything against the Pope, I told them in express and clear words that they had better not believe that I would on account of their money suppress a syllable of the truth.) After I had renounced the pension they saw that I would have nothing more to do with them, so they procured and betrayed (to the Senate), through a spiritual father, a Dominican monk, the manuscript containing in one letter my renunciation and receipt of payment, with a view of driving me out of Zurich. But the scheme failed, because the Honourable Senate knew well that I had not exalted the Pope in my discourses; so that the money had not affected anything in that direction; also that I in no way advanced their plans and had twice declined their pension; also that no one could from the past teaching accuse me of breaking my oath or impairing my honour. On these grounds the Senate declared me innocent” (i., 354).

Confirmation of these statements of Zwingli is given in this letter of Francis Zink, the papal chaplain at Einsiedeln: “A little time ago when I heard that you [the Senate of Zurich, to which body he is writing] were about to take up the matter of the people’s priest, Huldreich Zwingli, I met him twice in order to give my testimony. But now that I am sick and cannot come in person before your honourable body, I write to tell exactly all about it.… Huldreich Zwingli received for some years, while at Glarus, at Einsiedeln, and finally at Zurich, a yearly allowance from the Pope; but the sole reason why he has done so is his poverty and need, especially while with you at Zurich. And assuredly he would have lacked provision for his family if this support had been taken from him.… Nevertheless, this was so great a cross to him that he desired to resign his position with you, having it in mind to come back to Einsiedeln.… Moreover, it is perfectly evident that he has never been moved a finger’s breadth from the Gospel by the favour of the Pope, emperor, or noble, but always proclaims the truth and preaches it faithfully among the people. For if he had permitted himself to be turned aside to serve the interests of the papacy in greater measure he might have received one hundred florins a year, not to speak of benefices at Basel or Chur, but none of these enticed him. I was present when the Legate Pucci was frankly told by him that he would not for money advance the papal interests, but would preach and teach the truth to the people in the way which seemed best to him. Under the circumstances he left it entirely to the Legate whether he should grant the pension or not. Hearing this the Legate smoothed him down, saying that even if he [Zwingli] was not inclined to befriend the Pope, still he [the Legate] would befriend him: for he had not made the offer to turn him aside from his purpose [to preach the truth], but had had in view his need and how he might live in greater comfort and purchase books, etc.… I wished, therefore, to make this clear to you, not that I might absolve Master Huldreich Zwingli as if he had not received subsidies, but that you might know how he received them, and at what instance it was brought about, that you might see it from the right standpoint.” (This letter of Zink’s is quoted in the note to vii., 179.)

Zwingli was brought before the Senate to explain his inconsistency in taking the Pope’s money while attacking him, but this letter of Zink’s cleared him and he was not forced to resign. As Zwingli had no adequate support from his people’s priest’s office he felt the loss of the pension, but in the next year, 1521, he was made a canon in the cathedral and that made up for the lack of it and more (See vii., 182 sq., and p. 151).*

That, dear reader, is the truth and truly related. Zwingli, whether rightly or wrongly, accepted money from Rome in order simply to survive. When he was properly supported by Zurich, that became unnecessary. The gist of which is, if you don’t support your clergy, they may have to rely on pagans for survival.

________________

*S. Jackson, Huldreich Zwingli: The Reformer of German Switzerland (1484–1531) (pp. 114–116).

Zwingli Critiques a Review by Emser

Emser didn’t like Zwingli’s ‘Commentary on True and False Religion‘ (a work of true genius) so when he reviewed it (i.e., responded to it), said review provoked Zwingli to respond – in part –

You are so shallow, not to say foolish, that I am convinced you absolutely failed to understand what I wrote.

Few do read with the aim of understanding anything really.

In Which Zwingli Explains Why He Published his Sermon on ‘The Choice of Food’

Because his enemies were misrepresenting the oral presentation, Zwingli expanded and published it.

Because his enemies were misrepresenting the oral presentation, Zwingli expanded and published it.

I have therefore made a sermon about the choice or difference of food, in which sermon nothing but the Holy Gospels and the teachings of the Apostles have been used, which greatly delighted the majority and emancipated them. But those, whose mind and conscience is defiled, as Paul says [Titus, 1:15], it only made mad.

But since I have used only the above-mentioned Scriptures, and since those people cry out none the less unfairly, so loud that their cries are heard elsewhere, and since they that hear are vexed on account of their simplicity and ignorance of the matter, it seems to me to be necessary to explain the thing from the Scriptures, so that every one depending on the Divine Scriptures may maintain himself against the enemies of the Scriptures. Wherefore, read and understand; open the eyes and the ears of the heart, and hear and see what the Spirit of God says to us.

Today with Zwingli: His Adversary, ‘That Cumæan Lion’

“You should know that a certain Franciscan from France, whose name indeed was Franz, was here not many days since and had much conversation with me concerning the Scriptural basis for the doctrine of the adoration of the saints and their intercession for us. He was not able to convince me with the assistance of a single passage of Scripture that the saints do pray for us, as he had with a great deal of assurance boasted he should do. At last he went on to Basel [on 18 April, 1522] where he recounted the affair in an entirely different way from the reality—in fact he lied about it. So it seemed good to me to let you know about these things that you might not be ignorant of that Cumæan lion, if perchance he should ever turn your way.

“There followed within six days another strife with our brethren the preachers of the [different orders in Zurich, especially with the Augustinians]. Finally the burgomaster and the Council appointed for them three commissioners on whom this was enjoined—that Aquinas and the rest of the doctors of that class being put aside they should base their arguments alone upon those sacred writings which are contained in the Bible. This troubled those beasts so much that one brother, the father reader of the order of Preachers [i. e., the Dominicans] cut loose from us, and we wept—as one weeps when a cross-grained and rich stepmother has departed this life. Meanwhile there are those who threaten, but God will turn the evil upon His enemies.

“I suppose you have read the petition which some of us have addressed to the Bishop of Constance.… But I must return to Schuerer upstairs, where he is having some beer with several gentlemen and jokes will be in order.”*

_____________________

* S.M. Jackson, Huldreich Zwingli: The Reformer of German Switzerland. p. 170–172.

Today With Zwingli

On 16 April, 1522 Huldrych Zwingli’s sermon titled Von Erkiesen und Freiheit der Speisen was published in Zurich at the printing house of Froschauer. It was a greatly expanded version of the actual sermon preached shortly after the Lenten Fast was broken, with his approval. Unlike Barth’s Romans, this book really did fall on the playground of the theologians like a bomb.

On 16 April, 1522 Huldrych Zwingli’s sermon titled Von Erkiesen und Freiheit der Speisen was published in Zurich at the printing house of Froschauer. It was a greatly expanded version of the actual sermon preached shortly after the Lenten Fast was broken, with his approval. Unlike Barth’s Romans, this book really did fall on the playground of the theologians like a bomb.

Zwingli’s point was simple- the Church wasn’t authorized to heft upon souls requirements foreign to the requirements of the Bible. Its tradition wasn’t superior to Scripture; Scripture takes precedence over tradition.

In his own words-

[They] had not so strong a belief in God, that they trusted alone in him and hoped alone in him, listened alone to his ordinances and will, but foolishly turned again to the devices of men, who, as though they desired to improve what had been neglected by God, said to themselves: “This day, this month, this time, wilt thou abstain from this or that,” and make thus ordinances, persuading themselves that he sins who does not keep them.

This abstaining I do not wish to condemn, if it occurs freely, to put the flesh under control, and if no self-confidence or vainglory, but rather humility, results. See, that is branding and injuring one’s own conscience capriciously, and is turning toward true idolatry…In a word, if you will fast, do so; if you do not wish to eat meat, eat it not; but leave Christians a free choice in the matter…

But when the practice of liberty offends your neighbour, you should not offend or vex him without cause; for when he perceives it, he will be offended no more, unless he is angry purposely. … But you are to instruct him as a friend in the belief, how all things are proper and free for him to eat.

Today With Zwingli: ‘No, I Won’t Be at Baden’

In a letter to the Council of Bern, dated April 16, 1526, Zwingli sets forth in detail his reasons for refusing to attend the disputation in their city. In substance they amount to this: (1) That under the circumstances the safe-conduct offered him would be absolutely worthless; and (2) there was not the slightest chance of his obtaining a fair hearing.

Although Zwingli was absent, from the seclusion of his study in Zurich he virtually superintended the discussion on the part of the Reformers. For weeks previous, he labored unceasingly outlining arguments for the use of those who would represent him in the conference. The gates of Baden were strongly guarded by sentinels during the session, but means were found of eluding their vigilance, and letters were regularly exchanged each day between Zwingli and Œcolampadius. Myconius declares that “Zwingli labored more by his meditations, his sleepless nights, and the advice which he transmitted to Baden, than he would have done by discussing in person in the midst of his enemies.”*

_________________

*S. Simpson, S. Life of Ulrich Zwingli: The Swiss Patriot and Reformer (pp. 160–161). New York: Baker & Taylor Co.

The Day Zwingli Took Over the Carolinum, and Laid the Foundation for the Greatest Institution of Theological Learning of the 16th Century

Head-master Niessli of the Carolinum, named after Charles the Great, who had granted letters for an ecclesiastical foundation, at Zurich, was removed by death and Zwingli was elected as his successor, April 14, 1525. This institution had declined as a gymnasium, with the churches of the city, on account of the idleness and corruption of the religious and educational leaders; hence Zwingli sought to reform the Carolinum as well as the churches, as a necessary part of the great work of the Reformation.

Accordingly, on the 19th of June, in the same year, he substituted for the choir-service what he called “prophecy,” according to 1 Cor. 14, thus engrafting upon the Carolinum a higher institution which transformed it into a remarkably practical school of theology, ancient languages, and elementary science. It is here that Zwingli accomplished his greatest work, as an educator.

The school was in session every week-day, Friday excepted, and was opened at 7 o’clock in the morning, in the summer, and at 8 o’clock, in the winter. A month’s vacation was granted three times a year. The course of study centered on the Bible. The first hour, i. e. the “prophecy” proper, was given to exegesis, with some elements of systematic and practical theology to meet the wants of the Reformation. The second hour consisted of a divine service, in which the people of the city took part with the students, among whom were also town-parsons, predicants, canons, and chaplains.

Here the same Scriptures were treated again, but so simplified that the people could understand them; and we may add that the students themselves not only obtained a clearer knowledge from this repetition but they also learned, in a most practical manner, how to present the truth in their future charges. Friday was market-day, and the people from the country came to hear the preaching, which was largely intended for their special benefit. The afternoon of each school-day was devoted to the study of the languages and elementary science.*

We will return, on 19 June, to a further examination of this important theological institution.

_____________________

*Ulrich Zwingli, The Christian Education of Youth, trans. Alcide Reichenbach (Collegeville, PA: Thompson Brothers, 1899), 45–47.

Fun Facts From Church History: The Pig Eating Priests of Basel

On April 27th a friend informed Zwingli that some priests at Basel ate a sucking pig on Palm Sunday. The incident made quite a stir…*

As big a stir, it seems, as the sausage incident of Zurich.

______________

*S. Jackson, Huldreich Zwingli: The Reformer of German Switzerland (1484–1531).

On This Day, in Zurich, in 1525

The Council abolished the Catholic Mass in the Churches of Zurich. As Zwingli wrote that same year

Nothing, therefore, of ours is to be added to the word of God, and nothing taken from His word by rashness of ours. To this some one might here object: “Yet many have found rest even in the word of man, and still do find it; for today the consciences of many are firmly persuaded that they will attain salvation if the Roman Pontiff absolve them, grant them indulgences, enroll them in heaven; if nuns and monks tell beads for them, and do masses, hours, and other things for them.” To this objection I answer that all such are either fools or hypocrites, for it must be the result of folly and ignorance if one thinks one’s self what one is not.

Amen.

Today With Zwingli: The Abolition of the Mass

One more step remained to be taken and the church in Zurich would be completely emancipated from the Old Church, and that was to abolish entirely the mass. Cautiously, but without retrogression, Zwingli had for years steadily moved towards this goal. In 1524 he had won from the Council permission for the priests to dispense the bread and wine under both forms if they would. This, however, still maintained the connection with the old forms.

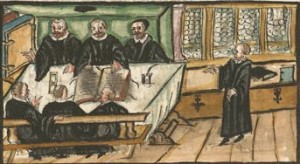

Judging that the time had come, and knowing that the friends of the ecclesiastical overturning were in decided majority in the Council of the Two Hundred, Zwingli and several other leaders appeared before the Council on Tuesday, April 11, 1525,—Tuesday of Holy Week,—and demanded the abolition of the mass and the substitution therefor of the Lord’s Supper as described by the evangelists and the Apostle Paul.

Opposition being made to the proposition, the Council delegated its debate with Zwingli to four of themselves, and their report being on Zwingli’s side, the Council ordered that the mass be abolished forthwith.

Consequently, on Thursday, April 13, 1525, the first evangelical communion service took place in the Great Minster, and according to Zwingli’s carefully thought out arrangement, which he had published April 6th.

A table covered with a clean linen cloth was set between the choir and the nave in the Great Minster. Upon it were the bread upon wooden platters and the wine in wooden beakers. The men and the women in the congregation were upon opposite sides of the middle aisle. Zwingli preached a sermon and offered prayer. The deacon read Paul’s account of the institution of the sacrament in 1 Cor., 11:20 sqq. Then Zwingli and his assistants and the congregation performed a liturgy, entirely without musical accompaniment in singing, but translated into the Swiss dialect from the Latin mass service, with the introduction of appropriate Scripture and the entire elimination of the transubstantiation teaching.

The elements were passed by the deacons through the congregation. This Eucharist service was repeated upon the two following days.*

On that remarkable day the Church returned, at least in Zurich, to its earliest practice – a practice long corrupted by the magical views of the supporters of the false doctrine of transsubstantiation.

__________________

*S. Jackson, (pp. 228–230).

Zwingli: On Statues and Paintings

The notion that Zwingli despised art is as ridiculous and uninformed as the belief, still widespread, that he despised music. Nothing was further from the truth. What Zwingli despised was the exaltation of anything above God or even towards God. Zwingli once remarked

The notion that Zwingli despised art is as ridiculous and uninformed as the belief, still widespread, that he despised music. Nothing was further from the truth. What Zwingli despised was the exaltation of anything above God or even towards God. Zwingli once remarked

Images which are misused for worship I do not count among ceremonies, but among the number of those things which are diametrically opposed to the Word of God. But those which do not serve for worship and in whose cases there exists no danger of future worship, I am so far from condemning that I acknowledge both painting and statuary as God’s gifts.

Don’t allow anti-Zwingli partisans and nitwits and uninformed angry Lutherans distort your understanding of the man. Read him for yourself.

Zwingli on Those Who Will Only Do, If In Doing They Receive a Reward

Those who so persistently demand a reward for their works, and say that they will cease working the works of God if no reward awaits the works, have the souls of slaves. For slaves work for reward only, and lazy persons likewise. But they that have faith are untiring in the work of God, like the son of the house. — Huldrych Zwingli

Those who so persistently demand a reward for their works, and say that they will cease working the works of God if no reward awaits the works, have the souls of slaves. For slaves work for reward only, and lazy persons likewise. But they that have faith are untiring in the work of God, like the son of the house. — Huldrych Zwingli

Zwingli’s Warning Against Folly

An appropriate warning for folly day-

Where persons assemble in social gatherings, every youth attending them should see to it that he go away morally benefited; so that he may not, as Socrates complains, always come home morally worse than he was before. He should therefore be watchful and diligent to follow the example of those who conduct themselves honorably and uprightly on social occasions; but, on the other hand, when he observes persons behaving themselves unbecomingly or shamefully, let him beware of imitating them.

Where persons assemble in social gatherings, every youth attending them should see to it that he go away morally benefited; so that he may not, as Socrates complains, always come home morally worse than he was before. He should therefore be watchful and diligent to follow the example of those who conduct themselves honorably and uprightly on social occasions; but, on the other hand, when he observes persons behaving themselves unbecomingly or shamefully, let him beware of imitating them.

Those, however, who are grown up and have become bold and fixed in their habits are hardly able to restrain themselves in this manner; therefore my advice is, that the youth should attend public gatherings, for social purposes, all the more rarely. Should a youth perchance be led into the folly of others, he ought by all means to turn away from it and should come to himself at the earliest moment. His reason for thus withdrawing from such association will satisfy those persons who know that his desire is, always to be intent on doing what is noblest and best.