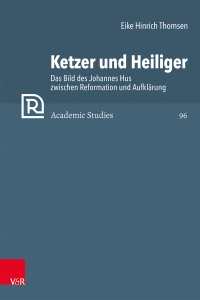

The European reformations meant major changes in theology, religion, and everyday life. Some changes were immediate and visible in a number of countries: monasteries were dissolved, new liturgies were introduced, and married pastors were ordained, others were more hidden. Theologically, as well as practically the position of the church in the society changed dramatically, but differently according to confession and political differences. This volume addresses the question of how the theological, liturgical, and organizational changes changes brought by the reformation within different confessional cultures throughout Europe influenced the everyday life of ordinary people within the church and within society. The different contributions in the book ask how lived religion, space, and everyday life were formed in the aftermath of the reformation, and how we can trace changes in material culture, in emotions, in social structures, in culture, which may be linked to the reformation and the development of confessional cultures.

The European reformations meant major changes in theology, religion, and everyday life. Some changes were immediate and visible in a number of countries: monasteries were dissolved, new liturgies were introduced, and married pastors were ordained, others were more hidden. Theologically, as well as practically the position of the church in the society changed dramatically, but differently according to confession and political differences. This volume addresses the question of how the theological, liturgical, and organizational changes changes brought by the reformation within different confessional cultures throughout Europe influenced the everyday life of ordinary people within the church and within society. The different contributions in the book ask how lived religion, space, and everyday life were formed in the aftermath of the reformation, and how we can trace changes in material culture, in emotions, in social structures, in culture, which may be linked to the reformation and the development of confessional cultures.

This wonderful collection of papers which were first delivered in 2021 at a REFORC meeting. The Leseprobe at the link above provides readers with a lot of the opening pages of the book including of course the TOC.

And don’t worry about the German of the website, the book is in English and the materials available are too.

The essays themselves are fascinating. I am particularly taken by Wandel’s ‘The Reformation of Time’ in which she investigates the ways that Missals were modified and adapted by the Reformed. Sometimes it’s the things you wouldn’t think about looking into that provide the most new information (or at least new to you).

Along with the usual historical and theological treatments we also find forays into the world of art and how the Reformation impacted it. Noble’s essay on Durer is a fascinating example of this field if investigation.

Not to be missed for any reason is Stjerna’s examination of women in the European Reformations. Their contributions are indisputably epoch making and significant and until recently they simply haven’t received the attention they deserve. Old white guys talking about old white guys has seen its time and now, thankfully, that time is past.

Other essayists also bring the importance of women in the Danish Reformation and beyond.

There are footnotes, bibliographies, and an index, along with a description of each of the contributors which finishes up the volume.

It’s true that of the making of books there is no end. Some (if not most, let’s be honest) should be ignored as they don’t deserve the time they get.

But others, like the present work, richly deserve a thorough reading and those who will are themselves richly rewarded.